Cousins, Critically: The Best of Series was explained in part 1 of the series. J.T. Moore would like to thank all those involved in the cumulative effort of Cousins, Critically, and all those who have taken time to read the exhaustive posts. It’s been a great year for television, film, music, and groundbreaking familial blogging, and Cousins, Critically proves it.

J.T. and M. Liam Moore Discuss The Year in Film and Music

J.T. Moore: This might sound weird coming from someone who runs an amateur blog about television, but movies are probably my favorite form of storytelling. In 2013. I saw maybe 5 or 10 movies that were released this year. Does that make me qualified to talk about the year in cinema? Yes, because the majority of those 10 movies were so damn good.

Gravity swept the nation, and for good reason. The film is an astounding achievement in technical filmmaking, and is an outright experience. As long as I’m talking about experience movies, I have to mention All Is Lost. A.O. Scott equated All is Lost to “an action movie in the most profound and exalted sense of the term,” which is the best way to put it. The amazing Robert Redford maybe speaks three times throughout the film’s entire 90 minute running time, and yet it remains captivating all the way through. But in 2013, I saw 2 movies that elevated themselves above all other movies in 2013.

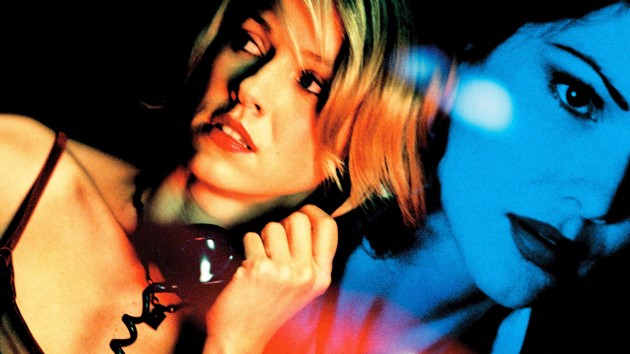

My second favorite movie of 2013 is Spring Breakers. I’m of the mind that Harmony Korine’s movie about four neon bikini-clad girls who let loose on Spring Break is a modern masterpiece. Or maybe a contemporary classic. Whatever you want to call it, Spring Breakers is a fantastic movie for the here and now. It might seem like Spring Breakers is some sort of perverse, morally depraved film made so creepy guys on the internet (not us) can see their favorite former Disney star in scantily clad clothing go crazy. It kind of is, but the film also functions as a brilliantly twisted social satire of our society’s obsession with things and how far we will go to get them (the film sums this up in James Franco’s glorious “Look at all my sheeyit” monologue). In twenty years, this movie will probably not be as good as I think it is now, but in the moment, Spring Breakers is smart, dark, profoundly unsettling, and will definitely make you think.

What’s that? You want a long-lasting, all-time classic that will make you think for the rest of your life? Look no further than 12 Years a Slave, my “favorite” movie of the year. I say “favorite” because it’s kind of hard to “like” this movie. 12 Years, which is the true story of Solomon Northup, a free black man from the north who gets kidnaped and sold into slavery, is much easier to think about than to “like.” The film is a brutal, unflinching look into Northup’s titular 12 years, and is so utterly different from any other American telling of slavery. There is no peace, restraint, or happiness in 12 Years, just sadness, regret and thought. In my short time on this earth, I have never experienced a more thought-provoking piece of art. Why haven’t we seen anything like it before? And how is one film able to embody the terrible and dispiriting struggle of one community? I will probably grapple with these questions for the rest of my life as a film-lover, and for good reason. 12 Years a Slave pushes the boundaries of what a film can be and can say, and is the best movie I’ve seen all year (and possibly decade).

What about you, M. Liam? Did you see any movies of note this year? If not what about music?

M. Liam Moore: I went to three movies this year, not counting holdovers from 2012 I saw at the Riverview. They are Gravity, The Hunger Bone and a horror film so nondescript I couldn’t even cull its title from a Google-provided list of the genre’s 2013 offerings. But on the basis of your description alone, J.T., I’m willing to crown Spring Breakers the Film of the Year. It’s a comfort to know I’m not the only one driven to mine the subtleties that yield a finer critical appreciation of these timeless, frolicking romps. I can’t wait to see if it stands up to my personal favorite, Bring It On, a turn-of-the-century look into the subculture of competitive cheerleading that featured pillow-fighting and, yes, a bikini car wash. There were moments I felt like I was sitting in the director’s chair.

I liked Gravity, and I’m glad I saw in the theater. Still, I’ve grown a little weary of watching George Clooney play the most interesting man on the planet 20 years before he was in Dos Equis commercials, and Sandra Bullock play the sheepish, smart, pretty-in-a-homely-sort-of-way heroine who struggles to overcome her self-doubt. It works in Gravity, of course, because the filmmaking is so innovative and breathtaking that the story is almost secondary to the experience.

I thought 2013 was a great year for pop music. Some of my favorite established artists – The National, Vampire Weekend, Arcade Fire – released new material, none of which disappointed. The Twin Cities hosted a slew of concerts I was excited to see, and I discovered all sorts of new sounds. Or sounds new to me, anyway; I’m always a little late to the party when it comes to music. What got your feet tapping in 2013, J.T.?

JTM: My favorite album of the year was Kanye West’s Yeezus. In my mind, the album has to be one of the most audacious popular rap albums ever produced. Of course, I am biased since I worship the altar of Ye, and think that Yeezus is his fourth perfect album. Even if he deemed us a flyover state on the Yeezus tour, I keep coming back to the album and every time I am completely taken aback. The beats and sounds on the album blare abrasively, and the lyrics are nasty and often times downright sickening, so Yeezus just shouldn’t work, but it ultimately takes control of you and doesn’t let go.

Admittedly, Yeezus most likely isn’t the foot-tapping type music you were looking for, because it’s its own type of thing. “Black Skinhead” might come closest to a radio hit, as it is the most rousing and energetic song on an album devoid of positive feeling or pleasant sounds. But it’s those unpleasant sounds that I find the most interesting. “Blood On The Leaves” is a very, very dark journey into Yeezus‘s nadir of dark descent, and “I Hold My Liquor” is a depressing, churning and almost profound experience, even if it finds the album’s truly awful explicitness at its peak.

I know I’m doing a terrible job pitching this album, and probably no one else besides myself enjoys listening to Kanye West writhe in his own musical nausea. This is because I’m interested in what Yeezus actually means to Ye himself. Is it performance art? Was he purging himself of all negative feeling before his impending fatherhood (maybe a technique you should try)? Or is the man at a point in his life where he actually thinks he is a god? All of this introspection, speculation, and stimulation comes from listening to a short 40 some minute trip called Yeezus, and that’s why it’s my favorite album of 2013.

M. Liam, I’ve noticed that one of your favorite albums of the year, Reflektor, has seemed to have been lost in the conversation in 2013. As we wrap things up, do you care to put up a defense for it?

MLM: The best defense is a good offense, J.T. The question, for me, isn’t whether Reflektor is a worthy album, but whether Reflektor is Arcade Fire’s best album yet. I think it might be. More than any of the band’s previous offerings, Reflektor distances Arcade Fire – in a sonic way, for sure – from its previous work. (Do you like rock ‘n’ roll music? Does James Murphy? Does it matter?) Reflektor also makes clear this isn’t a band that finds inspiration in success or comfort. The songwriting maintains an edgy sense of urgency, gnawing away at the album’s playful vibe. And that’s no accident. Contrast is Arcade Fire’s calling card. Previous albums transform loss into joy, extract triumph from hopelessness, find identity in suburban sprawl. Reflektor looks back – on colonization, on globalization, on the Greeks! – and celebrates the life, spirit and identity that survive in an increasingly sterile global cutlure. And best of all, it’s got a great beat that you can dance to.

The reviews I’ve read against Reflektor boil down to it being too long (a criticism lobbed at every double album) or too pretentious (a criticism lobbed at every Arcade Fire album). Minus the bonus track, Reflektor is shorter than The Suburbs. Sure, it’s pretentious, but do I really have to combat that charge in a series whose title includes a thoughtful pause? I don’t find it terribly overblown or preachy. Perhaps best of all, it captures some of the buoyancy Arcade Fire delivers to live audiences better than any band I’ve ever seen.

Speaking of concerts, Vampire Weekend’s brisk, jaunty show at the Orpheum this summer was the best one I saw all year, and their Modern Vampires of the City is undoubtedly their best work to date. Unlike Arcade Fire, this is a group that has taken a trademark sound – the world rhythms and neoclassical instrumentation, the hijacked hip-hop lyrics, the echoes of Buddy Holly and Paul Simon – and refined it, matured along with it. Modern Vampires is more contemplative and a little less ironic than the band’s previous albums. Bathed in a variety textures and sounds, it gets more rewarding with every listen.

I’m always late to the party when it comes to music, so my top 5 includes a lot of artists I already knew: The National’s Trouble Will Find Me is a hauntingly beautiful album that continues the band’s arty descent into Sad Dad Rock. Yeezus is egomaniacal brilliance, and for an album everyone sums up as “abrasive,” I found it surprisingly easy on the ears (albeit if you ignore some of the lyrics). Phosphorescent’s Muchacho is the kind of music I imagine Raylan Givens would play on his hi-fi.

And just for kicks, here’s in list format M. Liam Moore’s Top 5 Albums of the Year

1. Reflektor, Arcade Fire

2. Modern Vampires of the City, Vampire Weekend

3. Trouble Will Find Me, The National

4. Yeezus, Kanye West

5. Muchacho, Phosphorescent

And J.T. Moore’s Top 5 Songs of the Year

1. “Night Still Comes”, Neko Case

2. “I Should Live in Salt”, The National

3. “Blood on the Leaves”, Kanye West

4. “Step”, Vampire Weekend

5. “Get Lucky”, Daft Punk

Brendan Stermer Presents 2 Great Alternatives to 2013’s Musical Offerings

While far too many R&B “innovators” spent 2013 sulking in a cold soup of tired electronics and Drake-wave moodiness, Laura Mvula’s unclassifiable debut, Sing to the Moon, immediately set her aside from the crowd. The sound of the album is lush, organic, and fully-formed- but any honest description of Mvula’s unique style would contain far more hyphens than I’m willing to type. A graduate of the Birmingham Conservatoir, Mvula is a church choir director with a keen ear for jaw-dropping vocal arrangement that shines through at the most unexpected times. One moment impossibly tender, the next downright intimidating, Mvula’s mesmerizing vocal style sounds neither mainstream nor completely unfamiliar. “When the lights go out and you’re on your own/How you’re gonna make it through to the morning sun?” she questions on the album’s title track. Mvula, on the other hand, is rarely ‘on her own’ throughout the album’s 50-minute run-time, often accompanied by countless layers of “oohs” and “aahs” that weave through the spaces in sweeping orchestral arrangements. Even after months of near-weekly listening, Sing to the Moon still feels like the most captivating and imaginative record of the year.

Danny Brown is carrying around a ton of heavy mental baggage, and he does not hesitate to share even the most harrowing details. Throughout the first half of Old, the 31-year-old rapper teeters on the brink of insanity as he recollects horrors from his Detroit upbringing and confesses to deep insecurities about reckless lifestyle choices. Then, just as he vows to clean up his act, “Side B” tosses listeners head-first into a wacko, drug-infused clusterfuck of XXX-era proportions. This disorienting change of pace gives Old an element of riveting complexity, which defines the remaining tracks. What begins as an honest and thoughtful reflection transforms quickly into a whirlwind of graphic sex and drug abuse. Who is the real Danny Brown–the insightful and intelligent storyteller, or the rattlebrained drug fiend? Old is a fascinating documentation of Brown’s unfiltered, mid-life self-exploration. While Brown remains uncomfortably indecisive, the music that results is decisively unforgettable.